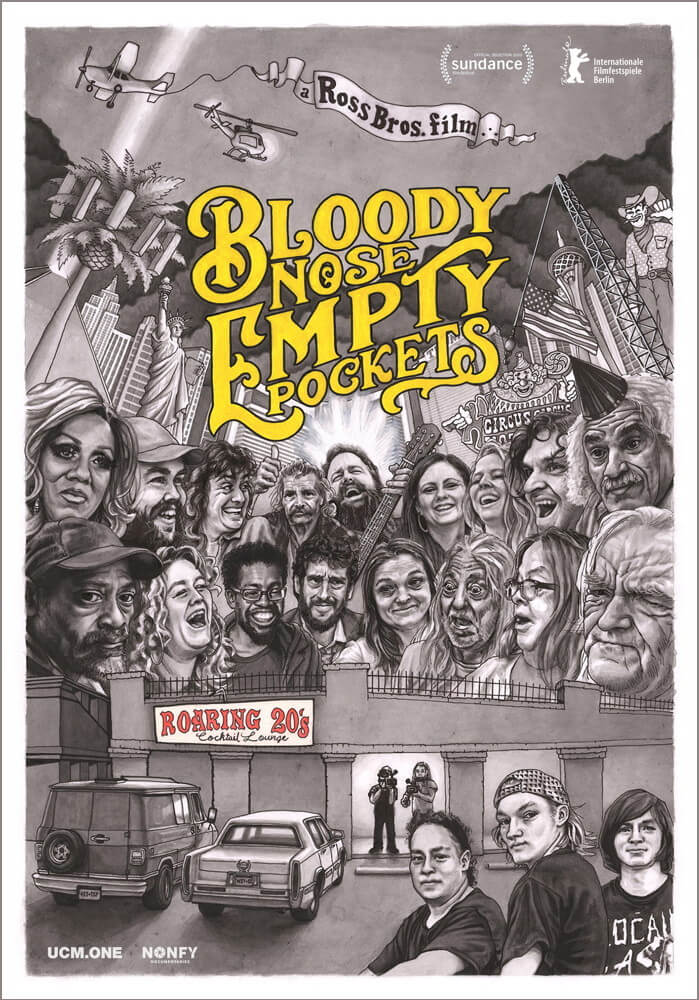

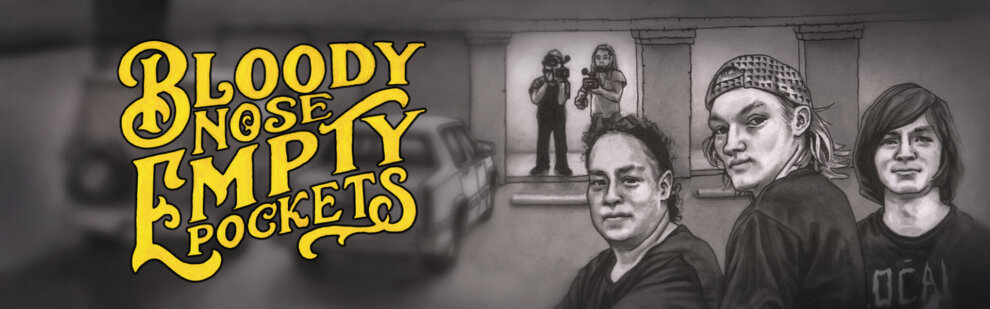

Original title: Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets

Directors: Bill Ross IV, Turner Ross

Producer: Michael Gottwald, Chere Theriot

Executive producer: Davis Guggenheim, Jonathan Silberberg, Nicole Stott, David Eckles, Minette Nelson, Matt Sargeant, Bryn Mooser, Kathryn Everett, Josh Penn

Featuring: Michael Martin, Cheryl Fink, Marc Paradis, John Nerichow, Lowell Landes, Ira J. Clark, Bruce Hadnot, Pete Radcliffe, Felix Cardona, Al Page, Rikki Redd, Pam Harperm, Shay Walker, Tra Walker, Trevor Moore, Kevin Lara, David S. Lewis, Kamari Stevens, Sophie Woodruff, Miriam Arkin

Cinematograpy: Bill Ross IV, Turner Ross

Visual Effects: Josiah Howison, Markus Rutledge

Editing: Bill Ross IV

Music: Casey Wayne McAllister

Production company: Department of Motion Pictures

Year of production: 2020

Genre: Documentary

Country: USA

Locations: Las Vegas, Nevada, USA; Terrytown, Louisiana, USA (Interiors [The Roaring 20s])

Language: English

Subtitles: German

Lenght: 98 Min

Rating: FSK 12

Aspect Ratio: 1:1.78

Sound: Surround 5.1

Resolution: Ultra HD (4K)